“Why are we being forced to remember an event like partition, that too on 14th August? Doesn’t it bring memories of unresolved grief? Isn’t it too much for our society to bear? What will it do except create more morbidity?” The question by a student left me baffled.

Her family and she focused on the positive, not the morbid and gloomy. She told me. “What is in that event except that?”

What had affected her the most was the Prime Minister asking people to remember our dead, the victims of the carnage of partition and asking everyone to give them ‘shradhanjali’ (tribute). “Why do we need to waste on a ceremony like that?” she had asked.

My mind had gone back years ago. My generation was taught in school that the partition was an unfortunate and inevitable byproduct of a struggle led by Gandhi towards India’s freedom. That it was unavoidable. What millions of school children had understood was that the decision to partition the country was through a national consensus and that the hands of our leaders were tied to accept the reality. Every school child in India is taught that the horrors of partition have to be seen in the backdrop of a nonviolent struggle that made us unique and produced the greatest apostle of nonviolence. The trauma of partition is added as a footnote in every history textbook.

As I learnt later, that the partition was a personal decision of a few people. That they worked it out amongst themselves and it was never debated in any public forum or any consensus built from the people. The only forum where it was brought about was the Congress forum on June14, 1947. Of the four hundred nominated members (not elected), only 200 attended and 129 supported. Even Gandhi had told Nehru that he was not consulted leading to a bitter exchange between the two. It led to the partition and an orgy of violence for which no explanation, no accountability was ever fixed for anyone.

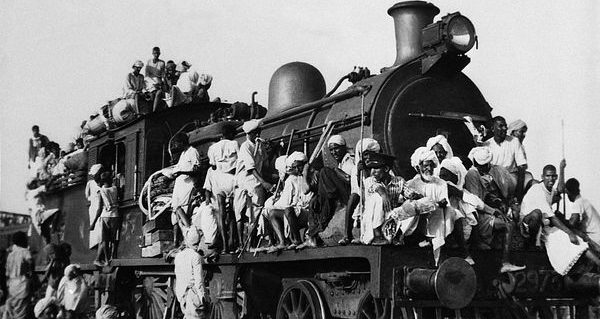

Subsequently as a nation, for seventy years, we never remembered the grief of partition and its trauma at a national level, relegating the biggest killing and mass murder of India in recent times to oblivion.

“Why is it when every year Japan remembers Hiroshima, Israel remembers the holocaust and other nations remember their dead, we shy away from remembering?” I had asked her.

Grief is a series of complex emotions, starting with denial and then through rage, bargaining and finally to acceptance with oneself.

History tells us acknowledging and commemorating grief through national ceremonies changes the dynamics of power in a people. It makes them aware, unites them and brings out their deepest strengths and makes them grow towards a mature society. What it does most is to create a society where accountability is demanded from leaders who can no longer hide behind false explanations or continue to lead its people blindly and remain above law. Acknowledging a nation’s grief and commemorating it makes the man on the street demand answers from its intellectuals on why certain things happened and who was responsible.

Going through grief ceremonies is also the greatest leveler of conflicts amongst people that have resisted solutions. Grief teaches us of our universality like no emotion. During the partition, different castes, different communities forgot their individual differences and ate together, lived together and supported each other. What bound them was loss of their loved ones, loss of their homes, their occupation and realizing the universality of it. If we had united people around this awareness for the last seventy years, who knows, India may have become a ‘vishwaguru’ (world leader). The denial of grief to a people, covering it with an explanation full of falsehood is perhaps the biggest crime that future generations will hold us accountable for.

What I notice is with a deep sense of poignancy is the grief as a theme entering our national consciousness and imagination. It reflects in the lives of our leaders at national level, in the Padma awards and in our debates. Our President is someone who went through a deep personal loss and converted her grief, a process called sublimation to serve the nation. This example of someone who came from one of the most remote and backward regions, who fought her losses in life will be an inspiration to millions. It can give rise to a new generation of leaders who will after facing overwhelming losses in lives turn to nation building.

The family of Chief Minister of Maharashtra was wiped out in a tragedy. What he did would have been inconceivable a few decades ago. Instead of withdrawing, he used sublimation to rise. The Padma awards show this new reality. Whether given to a scientist who was falsely accused of treason or to an unknown Indian walking barefoot in far off village for a social cause are the new symbols of an average Indian who overcomes his personal loss in the service of the nation. The unknown Indian may soon realize that his grief is not a defeating, a debilitating emotion, a time for withdrawl but to be converted for regeneration, healing and transformation. That Indian is the new ideal for all of us.

National grief ceremonies challenge the existing power dynamics in the society and can be dangerous as it awakens the people who no longer accept the old status quo. It tears up the curtain before the eyes of falsehood. Today, when one group is working in India towards remembering the grief of partition and asking why it happened, there are groups who wish to remain it hidden. I hope we realize it sooner than later so that an essential element of our national identity can be restored to us.

Commemorating grief by our society will be liberating. It will heal and bring a reconciliation for wounds that have been part of our identity for generations.

The last stage of the grieving process is ‘letting go’. It states that as a people we never forget but can change the way we feel about what was done to us. It makes us resilient giving us a memory to hold on to that is not distorted, or fragmented but gives rise to hope. I dream that my student who asked me this question and we as people of India finish that journey when we reach our hundredth year of freedom. I know I am not alone as I write this.

Rajat Mitra

Psychologist, Speaker and Author of ‘The infidel Next Door’