The last Hindu of Afghanistan not to leave is a priest. There is nothing surprising about it. It is a defining part of Hindu history and is our eternal identity.

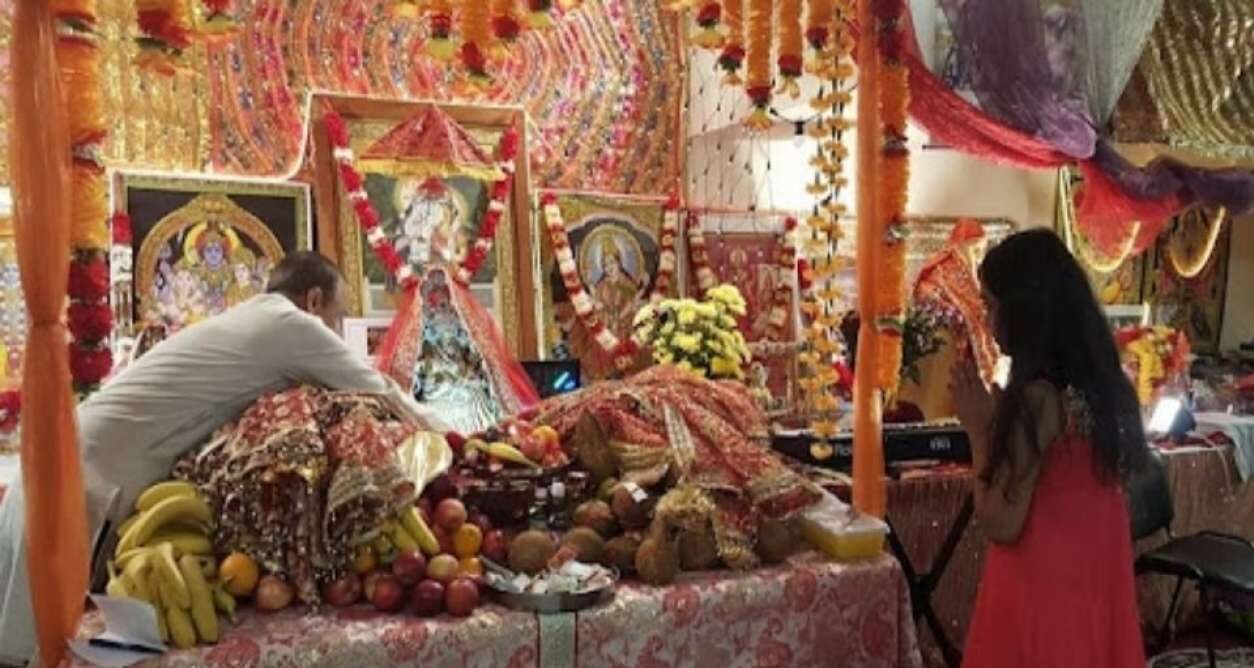

The picture of a lone Hindu priest praying to his deities and refusing to leave Afghanistan will stand as the defining and lasting image of Hindu civilization of how it was brought to an end. Afghanistan is a country that can put a banner saying ‘there are no more infidels left here’.

The image is apocalyptic and has a haunting quality to it. It cannot be described in words. It is the beginning of an apocalypse that began centuries ago between ‘the believer’ and ‘the non believer’ and whose end everyone sees as a matter of time. The final assault begins with the breaking down of a thousand structures whether the Bamiyan Buddhas, Martand temple of Kashmir or Somnath temple and Universities like Takshashila or Nalanda and ends up with one day the last Hindu standing alone in front of his temple refusing to leave. A story with a beginning, middle and end. The priest of the temple in Afghanistan awaits the same fate for being an ‘infidel’ in a conquered land that doesn’t accept him for his faith. It is a story that has the same perpetrator and the same victim each time it happens. The script, the narration remains the same.

The Hindu priest, unlike his counterpart from other religions has faced this end time and again. ‘To protect or not to protect’ is the question. Added to that can be ‘to run away or not to run away’. To both the Hindu priest down the ages has known his answer. What makes him stay back and not run away when everyone else does?

The reason why the Hindu priest doesn’t leave his temple or run away is because of a poignant relationship that he has with his deity and his temple. A relationship that is living and deeper than any man made relationship. For him, the deity is a living being, not an inert object, a vibrant being and for whom he is a protector and also that of his temple which is the abode. It is sacred, marked by an intensity, devotion and loyalty unmatched in any human relationship defying logic. It is something that both the Christian missionaries saw and also the Muslim invaders who understood that it cannot be destroyed easily. It is perhaps because of this relationship why Hinduism still lives today. It is a relationship where every attempt has been made to destroy it by the Christian missionaries and the Islamic invaders, the modern intellectuals calling it regressive and pathological. The only reason it has not worked is because it survives in oral history and memory of the Hindu priest.

It is a history that I came to know about while doing research for my book ‘The Infidel Next Door’. The chief protagonist of my book is a Hindu priest who doesn’t run away when Islamic militants attack his temple. He tells himself that he has a relationship with his deities and his temple and he cannot leave them.

Prior to this, like thousands of others, my image of a Hindu priest was based on Bollywood stereotypes and in conversations where he would be referred to with derision. Like children growing up in secular institutions, I had heard the story of the ‘lalchi priest’ of the temple who was always trying to cheat us. It was a story concocted and made up by those who couldn’t see his loyalty and devotion to his deity. He was shown as someone whose main task was to fix dates for marriage by falsifying information, one who arranged deals for sacred occasions, who could be bribed. Studying in so called ‘secular institutions’, it was the always the ever smiling, compassionate ‘father’ wearing a white robe who epitomized justice, honesty, values to be imbibed and who dominated our imagination. He was someone who rescued people, showed us the true path, whose fascination for young boys was an aberration supposed to be overlooked.

All this would have remained the same for me had I not met a priest at a refugee camp for Hindus from Kashmir. His name was Pandit Ram and he was the priest of a temple from Kashmir. Called Pandit ji by his fellows, he did ‘pooja’ everyday in the makeshift temple made by the members of the camp. He was alone. He was brought to the camp after he had been attacked and lying unconscious in his destroyed temple. In his delirium he had kept on saying he didn’t run away.

At that time I was trying to gain an understanding of the trauma of the members of the refugee camp. The violence, the rapes, the threats were the same as I heard from everyone and similar to what I heard at different camps I had come across the world. It was while having one such talk that someone remarked saying what he had gone through was nothing compared to what Pandit ji has gone.

“Which Pandit ji?” I had asked.

“You haven’t spoken to him?” he asked raising his eyebrows. Then he had stopped and said, “I understand, no one, whether a reporter or researcher wants to talk to him.”

“How is it any different for him?” I had wondered.

“Maybe you should hear him.” He had arranged a meeting for me. Pandit ji was hesitant at first. “What is there for me to say? Everything you must have heard already from others.” “Whatever you can tell me,” I said.

“Everyone had run away from my village. I was the only one staying back. Even the army came and asked me to leave. I told them I won’t. The deity is my mother. How can I leave my mother and our abode?”

Seeing my face he smiled and said, “I didn’t run away. It is against what I as a priest stand for. The deity has been protected by my ancestors. They didn’t run away when the invaders or the Kabalis came. So, why would I?” He asked.

“Then why are you here?” I wondered if I should ask him.

“The militants came one day and attacked the temple. I was sleeping inside and they burnt it. I was grievously injured lay there for two days before the army came and took me away. I said I won’t leave without my deity so they helped me carry the deity. After a few months of hospitalization I was brought here,” he said.

He took me to his room and next to it there was a makeshift room where he had installed his deity.

That is the day I understood why Hinduism survives and felt proud to be a Hindu. That is the day I decided to write a book telling his story.

There is no similar image of any priest from any other religion defending his religion like this that I am aware of. I wonder why is it that priest of other religions never had to go through what the priests of Hinduism went through, even in the very land of its birth. Why is it that there is almost no one to speak for the priest of Afghanistan and defend what he holds as scared? Why is it that the world doesn’t see his courage who won’t leave even when death is certain. These questions should be asked by every Hindu and every right thinking person. I believe in that answer lies an understanding unique to Hinduism of why it survived and also the role of the Hindu priest down the ages of how he has defended it.

Like the last Hindu of Afghanistan, the last Hindu of Kashmir will remind us of a permanent a defining part of Hindu history that can never be erased from memory. I ask that we teach this to our children and the coming generations about this story.

Rajat Mitra

Psychologist, Speaker and Author of ‘The Infidel Next Door’

PS: The book ‘The Infidel Next Door’ is written around the life of a Hindu priest from Kashmir who refused to leave his temple even when death was certain.