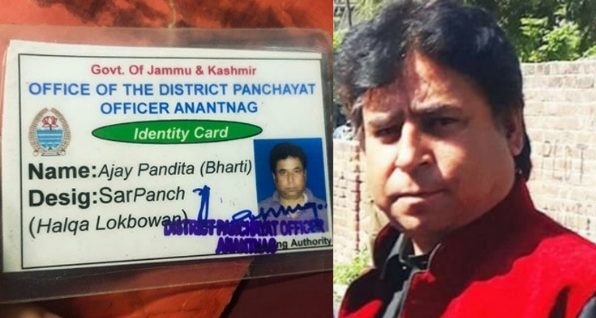

A Kashmiri Hindu and an old friend called me up a few days ago. We discussed the COVID19 scenario, the political situation created by Chinese incursion and then he asked me about the murder of Ajay Pandita. “It has affected me so much that I haven’t slept properly since then. It has affected my family too. For the first time in months I am at a loss. Can you explain why am I feeling this way?” he asked.

We talked for some time. As he shared his feelings, what came across to me was the utter sense of shock and unbelievability in his words. “Did you believe that after the abrogation of article 370 there could be still such brutal murders of Kashmiri Hindus?” he was asking. After a moment’s silence, he said, “Maybe I was wrong. After the abrogation and the way things happened, all my Kashmiri Hindu brothers had come to believe that no one will target us again like they used to do in 1989. That shell around us, that cocoon has busted with this killing. We remain as vulnerable as we were then.” Thanking me for the discussion, he hung up. A few days later he called me and said he had talked to several other friends. All had expressed a similar sentiment. It is as if the sense of vulnerability has come back to them. The shell of safety they had begun to build around them is broken. The question on their mind is that how could it happen when the reality of Kashmir is changing?

Some murders are more shocking, more disturbing than others. They shake our inner beliefs that we take as inviolate and which tell us the world, we inhabit is safe for us. The killing that is sudden and unprovoked tells us the world is no longer the safe place we assumed it to be. The murder of George Floyd is disturbing not just because of its brutality but because every Black man in USA fears being questioned and killed like that by police no matter what his station in life.

In 1995, while waiting at Amsterdam airport to board my flight, the television screen announced the murder of the Israeli Prime Minister, Yitzhak Rabin. A couple next to me had begun to cry hysterically saying something in Hebrew. As I learnt later, Jews cried that night not because their Prime Minister was killed but because it shattered their faith that after going through the holocaust, a Jew could ever kill their own Prime Minister.

Has the abrogation of article 370, the subsequent handling of the Kashmir issue, produced in the Hindus of Kashmir a similar conviction that the painful blood filled chapters of killings is over and met with a closure?

As a psychologist, I learnt about Kashmiri Hindus while working in prisons during my conversations with terrorists. The second was while working in refugee camps in Jammu. Kashmiri Hindus are unique in India. No other group of Hindus, I believe, has faced so much persecution and terror as they have over centuries. Perhaps that is why the need to exterminate the civilization of Kashmir is so strong in a certain group of people who would like Hinduism to become extinct. Kashmir remains a reminder of what Hinduism was in the past. The awakening of Kashmir will directly awaken the very soul of Hindus.

Research studies show that one terrorist killing is enough to create a circle of influence around a large number of people who stay permanently terrified and in a state of ‘learned helplessness’ for decades.

As I understood in my talks with terrorists, the goal today is not to kill more and more Kashmiri Hindus as was done in the past by invaders, but recreate that terror in their hearts that is as real and palpable as it was centuries ago. Called ‘trans-generational trauma’, it is today the biggest impediment in Hindu revival to autonomy and collective identity. Today, as many are coming to believe, a new Hindu identity can only be built around the collective memory of persecution.

When I worked in the camps for Kashmiri Hindus, the most predominant emotion that they shared was religious terror. The terror of being beheaded, the terror of being sawed into pieces after a rape, the terror of being killed and mutilated for solely belonging to their religion, was something that they discussed in almost every meeting. The terror often crossed generations, to centuries back when they were drowned for refusing to convert and to leave their religion because they were ‘infidels’.

Sarpanch Ajay Pandita had refused to give in to that terror that he believed was gone. He believed that they wouldn’t touch him. That he could stay in the middle of that terror, in the ecosystem that hated his religion, his beliefs and his status as a Hindu leader. It didn’t help that he belonged to Congress, a party for whom the Kashmiri Hindus do not even exist. He perhaps believed that the spirit that drove out half a million people thirty years ago wouldn’t apply to him because he was speaking their language, something that his party does without batting an eyelid. He perhaps also believed that the people had changed and a new era would emerge out of it. Maybe he even thought that if terrorists came looking for him like they did for Kashmiri Hindus in 1990, this time his neighbors would come to protect him. They would protest and stand by him. After all his party has been speaking on their behalf only. But it didn’t help. His killing shows the mindset hasn’t changed in Kashmiris in thirty years and will not in near future. The hatred, the vilification will remain as strong as before for every ‘infidel’.

As Toni Morrison says in her celebrated work, “…the very purpose of bigotry is to identify the other as an outsider and to separate him so that one can define one’s own self…” In Kashmir the Kashmiri Hindu has been ‘the other’ for far too long. The need to see him as ‘the other’ made the Kashmiri Muslim what he is. He drove him, the Kashmiri Hindu, out from his land, took away his home because that was the only way to define himself. That was the only way he could lay claim to the entire land by destroying the very civilization of Kashmir. In this there was no space or meaning for co-existence as long as the religion was different.

The reason Kashmir has been such a fertile ground for international terrorism has been due to its history, values and culture. It is impossible to understand this unless one understands the children who are made to grow indoctrinated in a culture of hate. The children were told to celebrate when the Kashmiri Hindus were forced to run away. The exodus of Kashmiri Hindus, the rape and the murder of Kashmiri Hindu women exists as narratives of victory over the infidel. They will tell you that it was their land and what their fathers and forefathers did was an act justified for this reason. When they pick up stones and hit the Indian army, they are told they are doing an act justified by their faith. With large scale violence, beheading and torture as the main imagery they grew up with forming their identity, how will we stop the death of persons like Ajay Pandita?

Today, more that the Kashmiri Hindu, it is perhaps the Kashmiri Muslim who needs to go to his roots and understand that it is he who is alienated from his land, his people and trying to define himself by detaching from his brother, the Kashmiri Hindu.

It is time to understand that abrogation of article 370 was no magic. The psychology of the people, the hatred and rancor need a far deeper understanding. I hope the tragic death of Ajay Pandita would once again to teach us that painful reality of Kashmir.

The exodus and the genocide of Kashmiri Hindus ranks as one of the greatest crimes of the twentieth century. Like all great mass crimes of history involving mass rape, violence and cultural annihilation, the perpetrators of Kashmir have evaded all accountability and still stand clean in the eyes of the world. They blame the survivors with half the world still believing them. History shows that unless the survivors rise from a slumber and relentlessly confront the perpetrators, no mass perpetrators come forward to take responsibility and this is true for the perpetrators of 19th January 1990. The men and women who rejoiced at seeing Kashmiri Hindus running away, watched them being sawed and killed should tell the world why they felt so and the world must acknowledge it as a genocide of a race who desired nothing more than to live in their homes and follow their religion. Till then, all peace will be elusive in Kashmir.

Rajat Mitra

Psychologist, Speaker and Author of The Infidel next Door

www.rajatmitra.co.in