“Sir, can I talk to you for few minutes?” It was Meenakshi (name changed), a student after my lecture at a university. “I need to talk. I have watched Kashmir Files and feeling deeply affected.” After talking about the movie, she told me, “Sir, how could people be so brutal and inhuman right next door to us while we all covered our eyes in denial and pretended it never happened? It has changed the way I thought of the behavior of people of Kashmir.”

“When you discussed about traumatic stress, violence and genocide, I told myself it happens to other people, far away from me and would never happen here. Now, I know it is not true.”

Post traumatic stress was one of the topics I was asked to talk about. The discussion of mass violence, genocide comes up in my lectures often but only in the passing. This is not an easy discussion for many students, young people. “It is a theme that always happens far away, not at my doorstep,” is often the reaction from them.

“You mentioned the Holocaust, the Cambodian genocide, the Rwandan genocide. I always believed it happened far away. I now know it has happened in India and been hidden from us.”

The history of human civilization is a history of mass discrimination and atrocities, racism and mass murders dominating the landscape. Lemkin, who coined the term genocide, found it extremely difficult to get a consensus on its definition because every nation from America or Britain wanted to hide its sordid past.

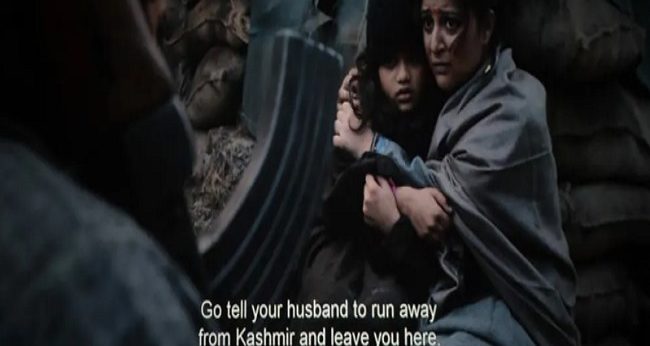

Meenakshi’s remark tells us about a change that is happening in Indian society. The Indian youth has begun to battle with a different reality which has surfaced overwhelming us with its portrayal of a stark reality the Indian psyche was not used to. The ‘The Kashmir Files’ has opened a raw wound in our society that lay hidden for decades. Its perpetrators were certain they were successful in hiding it and will be forever lost to the pages of history. It was a wound that lay cloaked in denial, its language in silence transferred from generation to generation.

The studies on trauma tell us that just like one trauma is linked to all other traumas of the past and the opening of one brings up all others, the coming of ‘The Kashmir Files’ has opened up all other traumas that we as a society have kept as covered wounds.

“What has the movie taught you?” I asked her.

“That I am not safe anymore in the faith I hold,” she replied. “That is what happened to Kashmiri Hindus. It can happen to me or to my children or grandchildren.” Speaking in short breaths, she replied, “When I asked my father after we watched the film, whether I should consider myself safe, he looked the other way. This movie has done what no other movie could do. It has ripped apart the illusion of safety.”

“But I am glad this illusion is over, Sir,” she said. “I have one more question. Can the two communities in India coexist? If people like Mahatma Gandhi couldn’t prevent partition and mass killing of Hindus so who will stop any other future violence and mass killing or a partition taking place?”

Talking to her, I didn’t realize we had been joined by few others. They were listening, an anxiety writ large on their faces. There was no anger, only an existential worry about survival that the movie has laid bare being a Hindu. “It is not an immediate issue of safety, but an existential one. It makes us question our basic assumption with which we have grown up, that we are a secular country and that keeps us safe.”

“My last question is that if the mosques in Kashmir valley blared slogans and their keepers exhorted their followers to be violent and threaten the pandits to leave or die, how was it that it remained a religious place anymore?”

“I feel as if a raw wound has opened up within me and won’t close,” she said before leaving. Meenakshi is not alone. From portals and posts, thousands of Indians are writing as if someone has ruptured a raw wound in them. We have all become a society in grief, the grief coming out in bursts.

The awareness in the present has come to rest on these inexorable truths. That it was not a few misguided people but the majority in Kashmir that planned and drove out the Hindus. All ages, families as a whole were involved and wanted their neighbors out of Kashmir. That children cried battle when they saw a Kashmiri Hindu and reported to the local commander. The second is what many Kashmiri Hindus say in a naive manner, that Kashmiri Hindus and Muslims lived in harmony and one day everything changed. For this brutality to be recognized as genocide there is but one prerequisite that it never happens in a day. The roots of genocide go back to centuries of hatred, malice and animosity.

Last but not the least is the ‘period’ it takes to document and understand the extent of a genocide. It may take a generation or two for a society to tell it to the world. The issues of safety and survival eclipses needs like finding justice.

“Will we get justice now?” I saw a Kashmiri Hindu ask after viewing the film. His tone of voice belied his confidence. What I wanted to tell him was we as a society also need something else apart from justice.

As a psychologist, having worked with survivors, I have seen that it is always safety that takes precedence over justice and not the other way around. The movie ‘The Kashmir Files’ has just done that, it has brought out the feeling of being unsafe, for our future generations that we have carried inside but never spoken about. Adding to it is the criminal justice system that has collapsed, the polarization of religious identity having taken us to a point where the average Indian now stares at an abyss. The Kashmir Files has taught us how unsafe it can be to be a Hindu at certain places and how dangerous it was to practice the Hindu faith and the Hindu way of life. It tells us that the Hindu religion and its way of life lie vulnerable, open to annihilation with impunity, can be annihilated with rest of world unaware. The seven exoduses, the partition, the extinction of Hinduism from Afghanistan and Pakistan is a reminder that the boundary is touching us soon.

In that respect, The Kashmir Files has opened the floodgates of a society steeped in terror and denial. No movie in the history of independent India has had the same effect. As suppressed emotions tumble out of the closet, many realize how they have been misled by those whom they trusted.

There is a need for healing for a people who have been survivors but who face demonization in the eyes of the world as perpetrators. This is not an easy path to traverse for any people or society to change its narrative from a wronged to one that depicts objective truth. I pray that out of this awareness takes place for a search for truth and resilience, where we will find intellectuals, healers, doctors, spiritual masters and professionals who will give a healing touch to a people who are awakening from a historical trauma.

“Never again” was the slogan that didn’t come immediately after the holocaust or even as a result of it (the world paying it hardly the attention it deserved) but because of the shock and awareness for a later generation that led them to question the foundation on which they were being told the truth. It is history repeating itself. This is equally if not more true of the Indian youth of today who need to know of the slavery, mass violence and atrocities unlike any other country that their forefathers went through. The independence that we got was not followed by a leadership that had the respect and courage to tell the truth to the generation then or the future generations. Therefore, the inner turmoil, the burning questions that the nation’s youth is facing today is deeply essential for our growth as a society as only going through it will they discover the dawn of a new era not marked by either lies or deceit. Then it will be a country that Tagore wrote as, “Where the mind is without fear and the head is held high.”

Rajat Mitra

Psychologist, Speaker and Author of ‘The Infidel Next Door’