It was my friend from Mumbai who told me an anecdote that can be compared to what best describes what is happening in Maharashtra today. My friend’s daughter, aged eleven and his son, aged nine, were fighting with each other as children do. Suddenly, his daughter screamed. When he went to investigate, he found his daughter in tears.

“What is it?” he asked.

“He called me a penguin and was laughing. I will call the police and tell them he called me so. Then they will take you away and you will know,” she had said.

“So, what is wrong if he calls you a penguin? It is a nice bird after all.” My friend had tried to pacify.

“Don’t you know?” daughter asked him. “It is the worst insult that we can use nowadays.”

My friend, taken unawares had to calm them by admonishing his son never to use the word again.

“You can be arrested if you address anyone like that,” she told him.

“Yes, I know,” his son had said. “But I told her what I truly think of her and no worse word than this came to my mind.”

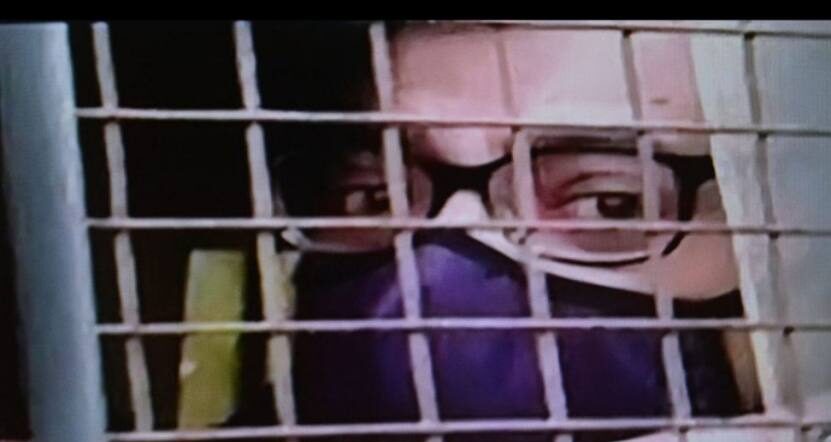

So, shall we name the present drama as ‘the revenge of the pe…n?’ A Shakespearean play. Part two. Act one. Curtain lifts at 6 am in the morning and unfolds before our eyes. A dead man’s handwritten note emerges suddenly and is given the fastest hearing in the history of Indian policing. His grieving, (sorry laughing this time as on internet) family asks them to investigate a case closed long ago by court. The suspect, a journalist who asks questions of the high and mighty, including why it is so difficult for some people to show empathy towards Hindu saints who are killed brutally is taken away by dozens of policemen. A dystopian reality but a cardinal sin for those who would like to see India converted.

A journalist in India could ask of the really important people ‘why pasta is better than roti’, the gold standard of measuring journalism in India. A journalist could not ask ‘why they never showed feelings for dead Hindu saints but could do it freely for other faiths?’

Talking of journalists, today there are perhaps few left in India, metaphorically. There are newsreaders and news anchors. Then there are journalists and more journalists who bag rewards and Padma awards. And lastly, there is Arnab. He is different. He does not read like a parrot from the screen like the rest. He shouts. He yells. He raises his voice and demands to know from the panelists if they are trying to hide something, an art in our country. Watching him at prime time, it is difficult to know what he or any of the panelists are saying, so much is the chaos. Yet, he is popular, perhaps the most popular of all. What does the mirror on the wall say?

I first saw Arnab on television more than a decade ago. A lanky young man with deep set eyes, he looked at each panelist intensely through his spectacles and spoke without a pause, never laughing. It seemed he was driven by some compulsion to attack everything they said and tried to elicit an answer they avoided. “This is not the way a journalist behaves in India,” I thought. A bull in a china shop maybe. The journalists I had seen, who wrote in papers were polite, docile, behaved almost like hospitality staff with a plastic smile permanently planted on their face. There was no fiery anger in their voice or in their pen, as they talked of any injustice. “Is he from Mars?” I had asked. “Where is he headed not adapting to political masters which is the first rule of survival for a journalist?”

As I watched him over the years, he seemed to be getting angrier each time with the issues our country faced. He was angry at the people who he thought were trying to hide, angrier at our society marked by indifference and fear. He seemed to provoke the panelists to elicit a reaction that was not coming. “Does he reflect an anger whose proverbial time has come for Indians?” I wondered.

I heard jokes of him too. A cardiologist told me he asks his patients to watch his show and they reported their low BP rising. A psychiatrist told me he asks his patients who have a difficulty confronting others to watch his show.

At the time he burst on the scene, Indian society was in chaos marked by disillusionment. The scams, the failed promises, the frauds a system that was failing had destroyed the aspirations of Indian people. Arnab tried to stall it and fill in the gap. He tried to ask questions a common man of India wanted to but never dared. He symbolized coming of age of the new Indian, one who is angry and questions the high and mighty, an Indian trait that lay buried and had not taken roots.

India has been a slave society for centuries. With the mindset of a slave, Indians found it difficult to confront and question. They found it easier to say ‘chalta hai’ and look the other way. Silence was the golden rule for survival. ‘Be silent and thrive’ was the mantra we Indians had adopted to live, first under the Mughals and later the British and one that did not change under the rule of ‘chacha’ and his descendants. The passivity in the garb of ‘ahimsa’ had flowed in our bloodstream and the rot had eaten the two most important qualities for a Rule of Law society – The power of imagination and the power to ask questions. To every injustice, Indians had one thing to say, “If it doesn’t concern me, why should I speak up.”

Arnab changed that rule. The average Indian began to ask questions and believed it as his right, unimaginable a generation ago. He told a nation not only to ask questions but also why they must do so. He became dangerous to those in power who believed that Indians will never speak up and remain a silent nation. That India will remain a nation where people do not want to know, an ostrich with its face hidden in the stand.

Having worked in human rights for two decades, I learnt that arrest is the last stage of any investigation in a Rule of Law society. Only under a fascist government can an unarmed journalist be picked up by policemen carrying guns and taken away by force. Who is taking a leaf out from Nazis’ rule book in India? Ironically, those called fascists are speaking up for him. Who is the true fascist in preset day India then?

India has long been under a deathly silence as long as memory goes. Many events such as Jallianwalla Bagh, the Partition, the Emergency, all perpetuated a culture of silence that never left us. That silence, I believe, is going now and that is why his arrest.

Arnab’s arrest reminds me of two sayings.

One is that how dangerous it can be to speak up in present day India against those who believe it is their birthright to rule our country.

The second is the old saying where I have changed the words a little. “When they came for the Palghar sadhus, I kept silent. When they came for SSR, I kept silent. When they came for Arnab, I tried to stay silent. But when they came for me, they took me away because there was no one left to speak for me.”

Rajat Mitra

Psychologist, Speaker and Author of ‘The Infidel Next Door’